Monica Quezada: Using Satellite Imagery to Map Irrigated Areas in Ahuachapan, El Salvador

During the summer, many IAD Masters students can be found working with an organization in another country and conducting research. Due to the Covid 19 pandemic, traveling was not possible this past summer which meant students and organizations had to get creative.

I had previously planned to work with Catholic Relief Services Raices program in Ahuachapan, El Savlador. Raices is a long-term program that aims to implement water-smart agriculture at the landscape level. As part of the program, CRS is working on expanding farmer access to irrigation technologies. CRS was seeking help with targeting irrigation expansion but they had limited benchmark data for the areas already under irrigation.

Together with the Raices Director, Paul Hicks (also an IAD alum) and two of my committee members, we decided that benchmarking irrigated areas in the Agua Caliente watershed where CRS’ efforts are focused, would be an ideal place to start. Aside from being in line with CRS program goals, another advantage was that the project could be carried out remotely.

I began meeting regularly with local CRS staff to understand what data they had at their disposal and to determine how we would go about getting necessary data. Initially, we believed we could map irrigated areas using irrigation permit data collected by the Ministry of Agriculture. However, our many attempts to acquire irrigation permit data were unsuccessful.

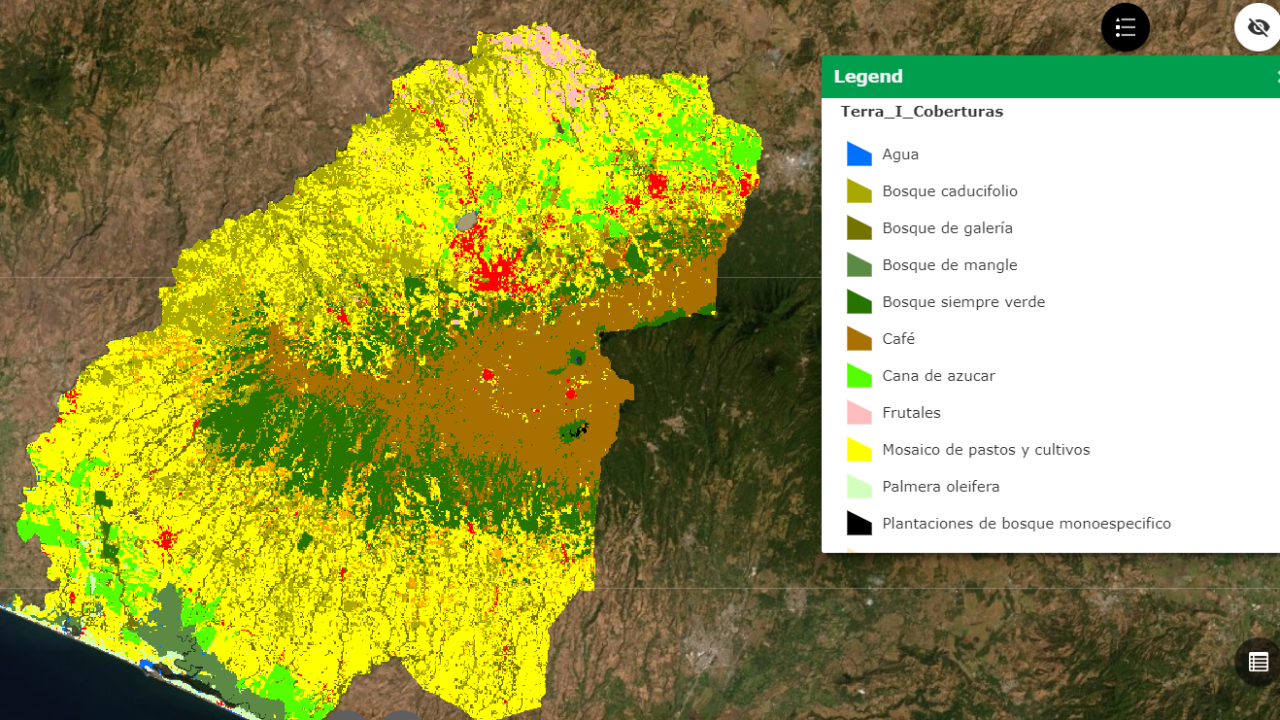

Our current strategy is to use satellite imagery to identify irrigated areas. CRS has already developed a land use map so we are building onto that work. Current efforts are focused on 3 landcover classes: sugarcane, fruit trees and annual crops which includes maize, sorghum and horticultural crops. My initial efforts focused on identifying irrigated areas using a greenness index such as the Normalized Differenced Vegetation Index (NDVI). However, I learned this measure is not ideal for perennial crops that do not experience the same ramp up and decrease in greenness that annual crops do. When dealing with perennial crops, it makes more sense to use an index that captures water content or evapotranspiration (ET). Luckily, we have ready access to data that is directly related to evapotranspiration. ECOSTRESS data, which just became available in July 2018, measures evapotranspiration at 70-meter spatial resolution, which translates into half-hectare pixels. We hope that by pairing this with precipitation data from 3 weather stations in the area, we can successfully identify irrigated areas. If an area is rainfed then we expect ET=precipitation. In an irrigated area, we would expect to see ET > precipitation. In order to validate this method, the classification is compared to ground truthing points (known irrigated and known rainfed fields) to see how well it is able to identify one vs the other. With this output, CRS will be better able to target areas for irrigation expansion.

While this project has not been without its challenges, I am very grateful that I was able to find a way to collaborate with CRS. When I first started learning GIS last year, I thought it was mainly used for precision agriculture and for farmers with the means to pay for this data. However, this project and collaboration has allowed me to learn about the ways in which GIS and remote sensing can be applied to natural resource management and improved program targeting in developing countries.

This research was made possible through funding from the Henry A. Jastro Graduate Research Award, The Global Fellowships for Agricultural Development (GFAD) program, and the Blum Center for Developing Economies Poverty Alleviation through Sustainable Solutions (PASS) project awards program.